'If organizations just sit around waiting for more women to apply, or to ask for promotions, it's not going to happen,' says B.C. academic

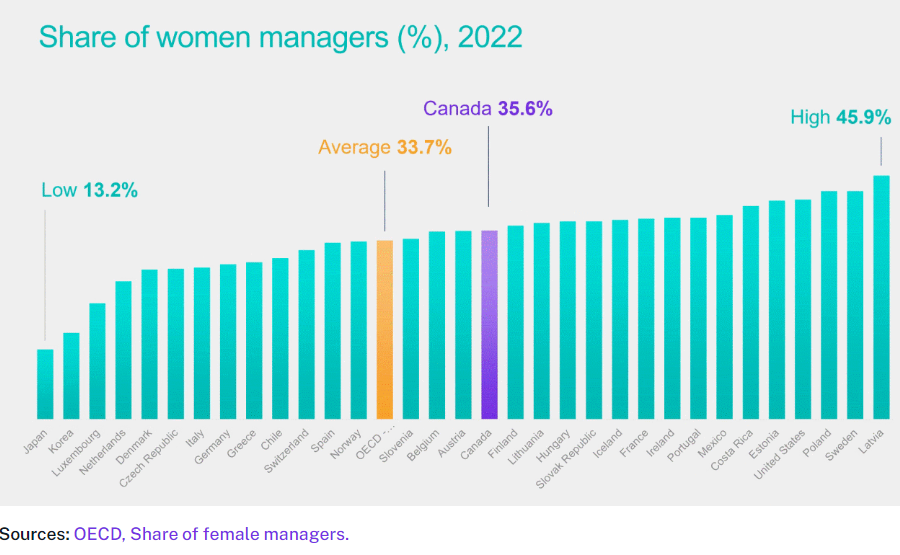

As the world celebrates International Women’s Day on March 8, the Canadian Chamber of Commerce released dismal news for women in Canada: they are less likely to be managers than women in almost of all the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.

If the pace of women being promoted into management continues as it is, the Chamber reported, Canada won’t reach gender parity until 2129. Sitting at 16th in a list of 37, Canada falls behind the U.S. (4th), Mexico (7th), Ireland and France (9th, 10th).

Dr. Samantha Dodson, Research Fellow at the Montalbano Centre for Responsible Leadership Development in the Sauder School of Business at U.B.C., said that the numbers could be attributed in part to Canada’s relatively strict pandemic lockdown rules, which might have led to more women leaving their jobs and then not returning.

“That could certainly have played a role. But there is the sense that women that left the workforce are starting to come back,” Dodson said. “Anytime women have to leave the workforce for a given period, that's going to hurt their abilities to advance in most organizations, whether it is because of the pandemic, whether it's if you have a child or some other family event or emergency, oftentimes women do shoulder that, which makes it harder for them to grow up the ladder.”

Women ‘shy away’ from leadership roles

However, Dodson shared, there are many legal and regulatory structures in place in Canada that should protect them from such barriers, such as strong support for taking family leave and protection from discriminatory job exclusion.

Dodson’s work focuses on the idea of power, and identifying why women might “shy away” from pursuing leadership roles. Her research has found that women don’t anticipate having power when they do make it into leadership or management positions, a tendency which could be conscious or subconscious.

“They don't want to move up in their organization, and there's a lot of reasons for this,” she said. “If you were concerned that if you took on a role that people won't listen to you, your opinion wouldn't be valued, you wouldn't be able to influence other people – would you be less interested in being in that role, if you just thought you were going to get trampled on?”

Messages of inclusivity promote more women into management

The positive side of this research, Dodson said, is that there is a clear remedy.

“If managers and other people in these leadership roles can share with women their stories of feeling supported, feeling like they were listened to and that they had influence, it increases women's desire to apply for the role,” she explained.

“That assurance is enough to change the minds of some women who might have been hesitant to pursue leadership before. It increased their interest.”

These messages can be in the form of mentorship programs where high-performing women who are interested in leadership can connect with other women who are in leadership to gain their perspectives.

Testimonials can also be effective in encouraging women to pursue promotion into leadership roles, either in job postings, on the company website or internal messaging.

Interestingly, this messaging is effective whether it is coming from men or women, Dodson said. The important thing is bridging the gap between the leadership group and the rest of the workforce, making the act of applying for promotion less intimidating.

“It would probably be more effective if it was a woman, but if they can at least signal that the culture of leadership is such that people get listened to and cared about, whether it's a man or a woman, it’s equally effective,” she said. “They get confirmation that their initial expectations could be wrong, and that it might actually be okay to be there.”

Leaders must be proactive welcoming women into management

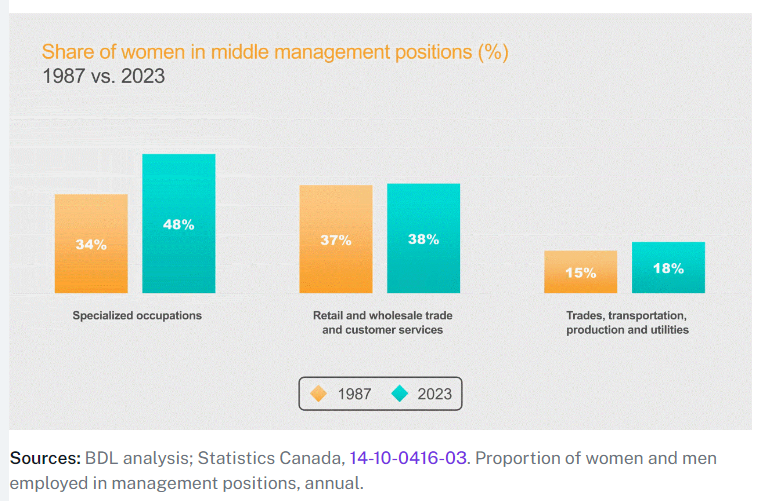

Canadian women are lagging behind in all three levels of management, the report revealed; middle management, senior management and board directorship all showed “dismal” progress in recent decades.

Because of this, upper management needs to take active roles in promoting and encouraging women to advance their careers, Dodson said.

“There's going to be institutional forces that are going to make them feel like they can't, or that it's not safe, or they just don't want to because they don’t want to be in that kind of environment, and so that's on managers and leaders to fix those problems,” she said. “You need to be active in your efforts to create spaces that women feel safe in, where they feel like they can do their best work in … put in the effort to recruit them.

“If organizations just sit around waiting for more women to apply, or to ask for promotions, it's not going to happen.”